Here’s another instalment in my occasional series looking at architects who were active in Nottingham at around the same time as Watson Fothergill.

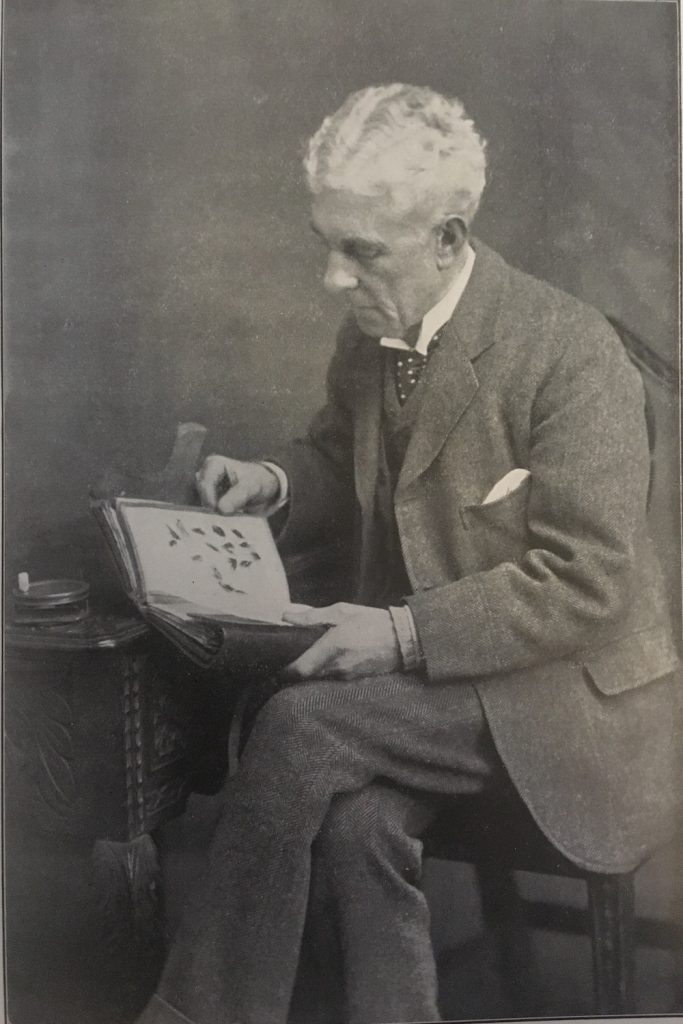

Albert Nelson Bromley (1850-1934) is probably best known for his long involvement with Boots The Chemist, but he was responsible for many buildings in Nottingham ranging from schools to shops, warehouses to telephone exchanges.

Albert Nelson Bromley was born in Stafford in 1850, he was very young when his father died and the family moved to Nottingham to live with his uncle, the architect Frederick Bakewell (among his notable buildings – Nottingham School of Art, now NTU’s Waverley Building). After going to school in Nottingham and Lincoln, Bromley joined Bakewell in his office on Pelham Street and was articled as a pupil. Having joined RIBA as a fellow in 1872, he was on the point of moving to Manchester to take up a post when it was suggested that he spend some time on the continent sketching buildings.

Bromley spent 14 months in 1872-73 on an extended architectural sketching tour of Europe. In all, he visited 90 towns including Bruges, Chartres, Heidelberg, Prague, Venice, Siena, Athens and Constantinople in 9 countries. (Belgium, France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Greece, Turkey and Holland).

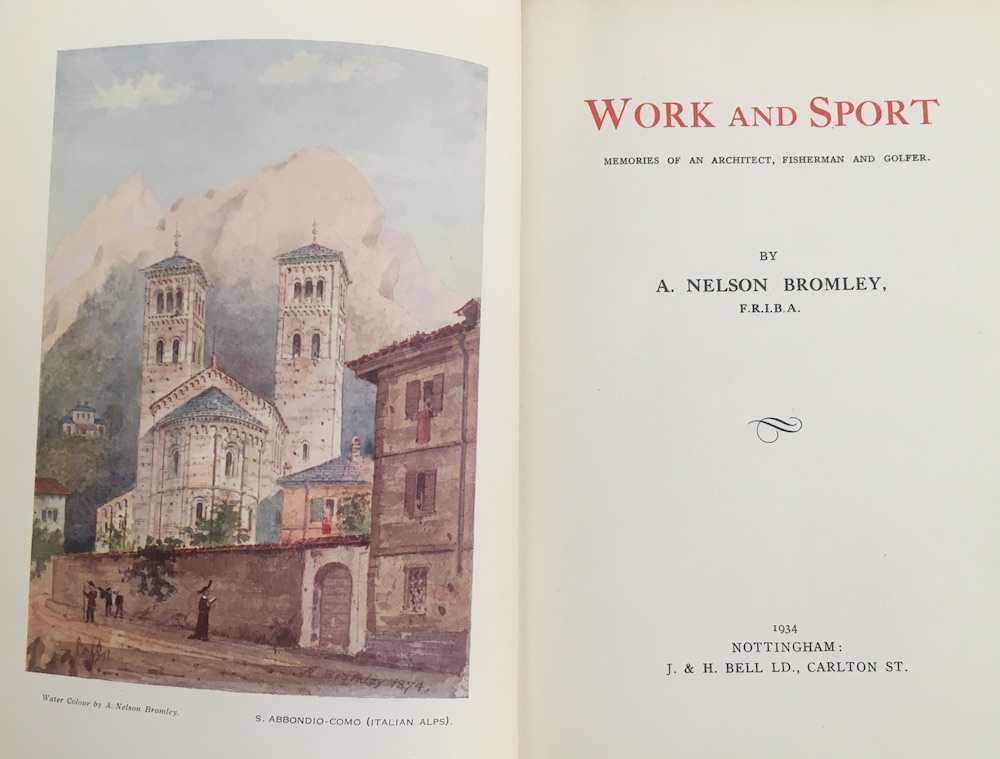

In Work And Sport: Memories of An Architect, Fisherman And Golfer, which was published in 1934 towards the end of his life, he states that the object of writing the book was “mainly to reduce to readable proportions the Continental Diary of my Architectural travels during 1872-3.” On departing for his travels he was advised by an unnamed ‘Artist of Architectural subjects’ to:

“Go as an Artist with a knapsack on your back… the simplest thing – look as dirty as possible – don’t shave – wear a large slouch hat and smoke a very black pipe, you will go everywhere for half price. The guides will not bother you and the pimps and gay ladies will not give two-pence for you, as an Artist has no money.”

Without foreign languages, Bromley recalls being somewhat lonely and miserable, having left behind “a very nice girl” who was to become his wife (Elizabeth, whom he married in 1878). He did eventually meet some “rough diamonds” who were willing to stand him a drink. A sample encounter: ‘Oh I see you are an Artist – come and have a drink. Well, you will not get much out of that job.’

‘No, I am studying for an Architect.’

‘Oh, them blokes, well, you’ll make a bit more out of that.’

The rather hazy recollections of people and places (mostly places) in the ‘Work’ section of the book are accompanied by plates of the watercolours that Bromley made of various buildings on his travels. The rest of the book is mostly concerned with fishing. There is frustratingly little about the buildings that Bromley worked on himself.

On his return to England, he re-joined his uncle, Frederick Bakewell at his office, at 5 Victoria Chambers, Victoria Street. By 1875 they had moved to 3 1/2 Weekday Cross. One of their significant commissions was an early instance of Council Housing, the Victoria Buildings (Bath Street). Their partnership was dissolved on 15 May 1876. Bakewell died in 1881, aged 57.

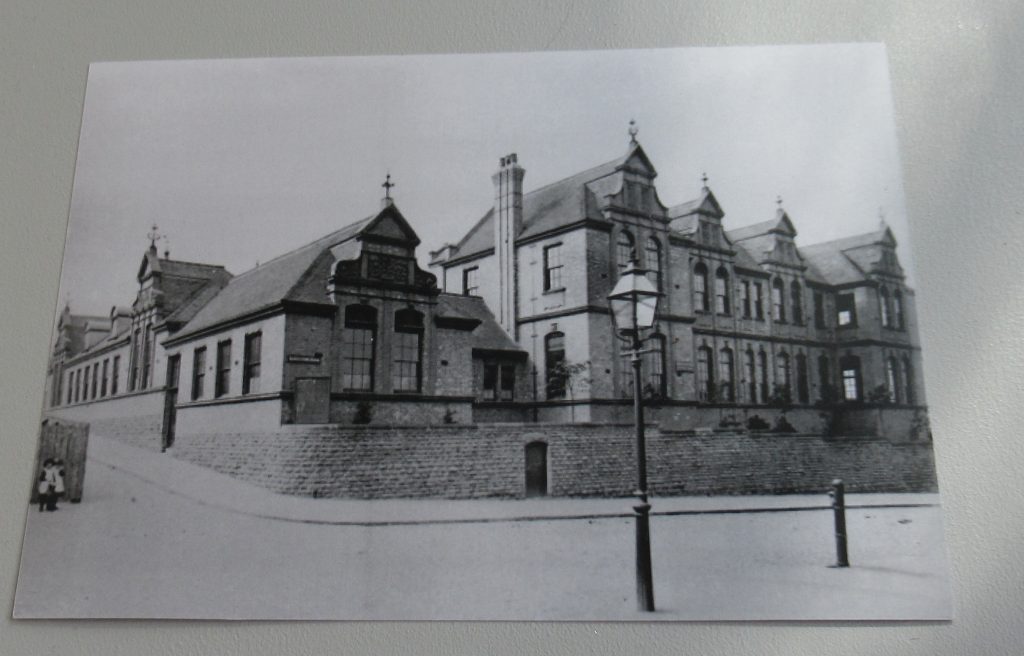

Bromley went on to become the principal architect for the Nottingham School Board, after being chosen as one of the initial four practices to be commissioned to build schools (see blog on Abraham Harrison Goodall). He did some work for the Nottingham Tramway Company and built houses in Sneinton and Bulwell. Hucknall Public Library was built to Bromley’s design in 1885-6.

The precise date of the houses Bromley built in The Park Estate, including his own at 15 Newcastle Drive (originally 24 Pelham Terrace) are not confirmed (Wikipedia cites an early estimate of 1878, but The Nottingham Park Houses project plumps for circa 1890).

Bromley’s work in The Park seems to be concentrated on Newcastle Drive. He not only built numbers 15 & 17, but it is also now proven that he built 21 & 23 (records exist in the contemporary architectural photographer Bedford Lemere & Co’s archive). Glendower, the house at 27 Newcastle Drive may also be by Bromley (rather than by Watson Fothergill as is often claimed). Stylistically it has more in common with its neighbours and it lacks the richness that typifies Fothergill’s other houses in The Park. (See notes on The Park Estate in Darren Turner’s Fothergill: A Catalogue of The Works of Watson Fothergill).

Glendower was built for William Foster (perhaps the WF inscribed on the front of the house leads to connections with Watson Fothergill?). I’ve found evidence (Nottingham Journal 10 Nov 1881) that Bromley tendered for builders to work on a furniture depository for Foster’s Furniture company Foster and Cooper in 1881 and I personally don’t think this building is by Fothergill either.

Bromley was steadily busy through the 1890s, with buildings which include an office and telephone exchange for The National Telephone Company in George Street in 1898, look for the candlestick telephone motif.

Outside Nottingham, there was the baroque classicism of Telephone House built for the same company in London (1898-1902).

Other buildings still standing in Nottingham include a wholesale fruit store for Buckoll, King & Co on Parliament Street (now Argos) and offices for Wells and Hind on Fletchergate (now part of the Ibis Hotel development). Deep red terracotta facings are a noticeable feature.

Bromley is possibly best known outside Nottingham for his work for the Boots Company. He began this association with Alterations and Additions to their Island Street works in 1895. This lasted into the 1920s with stores being built around the country. In Nottingham, the company’s flagship store on the prime site of High Street and Pelham Street (now Zara) was designed in a glazed light terracotta with an air of Art Deco in the ornate shapes of the shop windows.

Details of the Boots No. 1 Store (now Zara). Note the various rather muscular putti – something that T. Cecil Howitt also liked to add to his buildings

In 1903, Thomas Cecil Howitt joined Bromley’s office as a pupil, by now they were located in the Prudential Buildings on Queen Street. Work for Boots continued into the 1900s – including the shop and cafe Boots Store No. 2, 1906, now The Embankment pub. Bromley also worked on The National Provincial Bank (now Virgin Money) 1910 (demolished and rebuilt when the Council House was built by Thomas Cecil Howitt circa 1927) and additions and alterations were made to the Long Row/ Market Street Griffin & Spalding department store (until very recently Debenhams) 1910, with more work on the store in the post-WW1 years.

Harry Graham Watkins joined the firm and became a partner and they ran a London office for a time – Thomas Cecil Howitt notes on his CV that he was the manager in 1908. The majority of their work was probably on bank branches, Boots stores and Telephone Exchanges around the UK. The Boots stores were often designed with a nod to the local vernacular or historical styles. An incomplete list of branches includes Beeston, Derby, Exeter, Gloucester, Kingston-on-Thames, Lichfield, Shrewsbury, Winchester and York. For more on Boots stores around the UK, read the excellent Building Our Past blog.

Just before WW1 Bromley visited New York, Boston and Washington in the USA. He noted that the skyscrapers in New York assumed ‘the appearance of a fretful porcupine.’

In the 1930s, Watkins retired and the practice was joined by Bromley’s grandson Thomas Nelson Cartwright and the rather elusive Thomas Herbert Waumsley. Bromley celebrated his 80th birthday in 1930, so how active he was in the new partnership is debatable. Cartwright went on to join the firm established by Robert Evans Jr in a partnership that became Evans, Cartwright and Wollatt in 1948.

Albert Nelson Bromley died in August 1934 at his home 15 Newcastle Drive. His buildings, as Ken Brand notes, are neither distinctly Victorian nor blatantly Modern(e) but there is a certain feeling of neatness and proportion. His Evening Post obituary summed up his involvement in the appearance of the city:

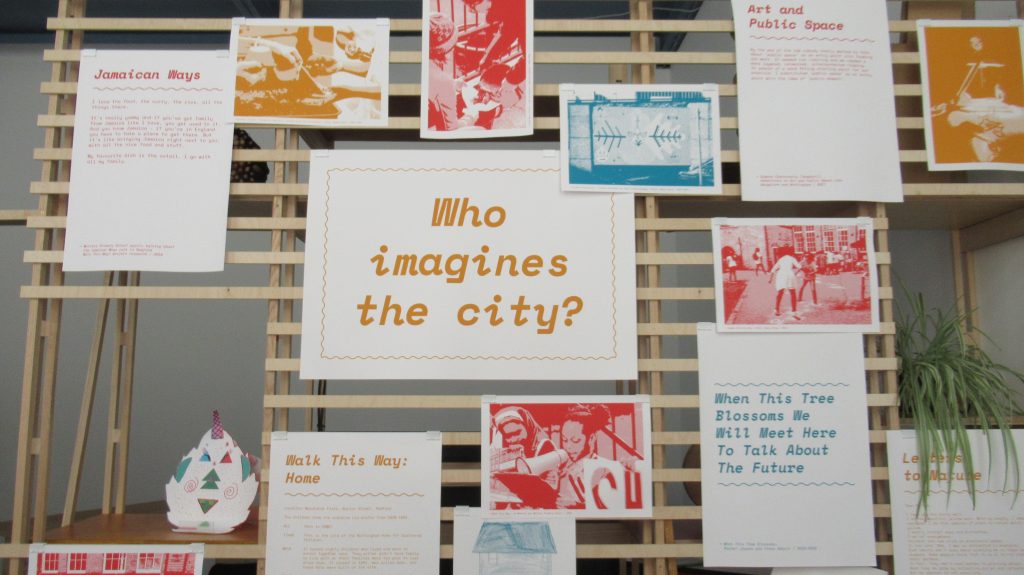

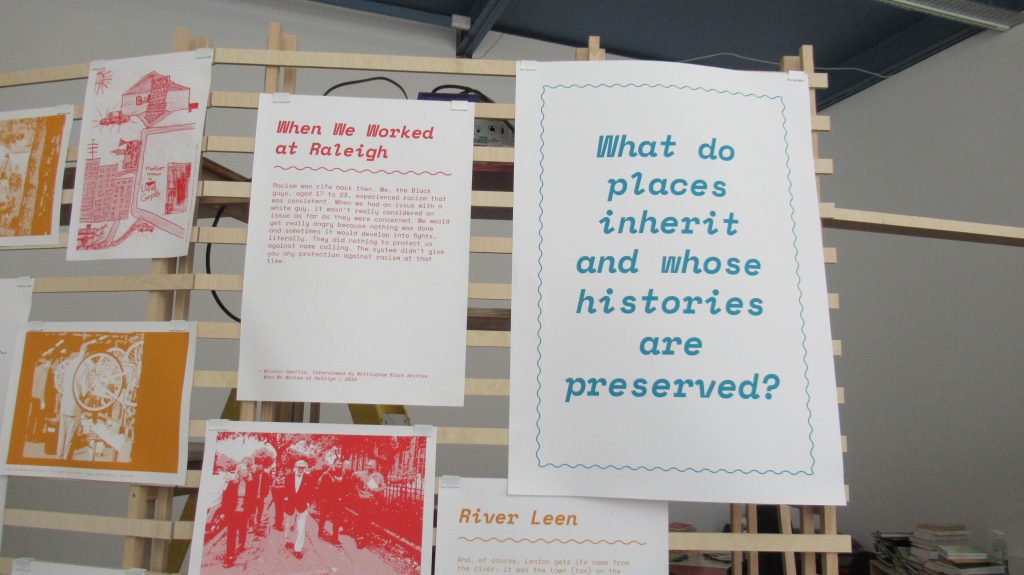

‘…Mr Bromley was as keenly concerned about the preservation of the amenities of town and country as he was about his personal affairs, He strove… to arouse the public mind to the loss of beauty caused by such blots as ribbon buildings, hideous advertisements, ugly or inharmonious buildings, and the demolition of historic places.’

Obituary, Nottingham Evening Post 1934

A more in-depth look at A. Nelson Bromley’s work is available in the redoubtable Ken Brand’s article for Nottingham Civic Society.

Learn more about the architecture of 19th and early 20th Century Nottingham by booking a walk with Tour Guide Lucy Brouwer.