Once again I’ve made it inside one of the Watson Fothergill buildings that features on The Watson Fothergill Walk.

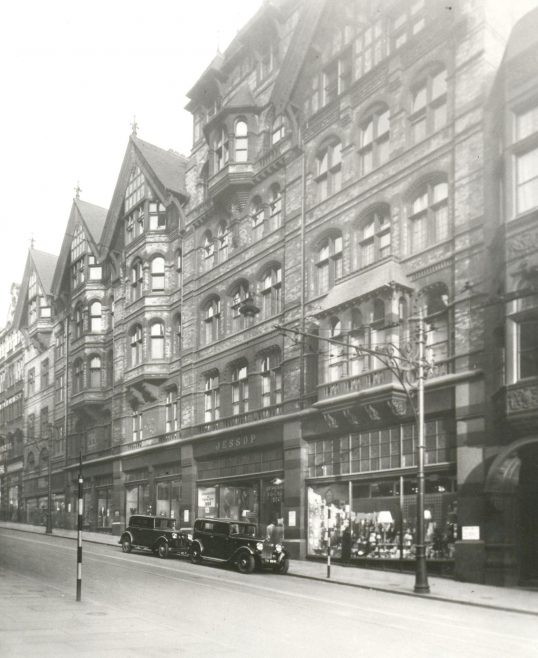

Thanks to Alec Frusher (a keen Nottingham food blogger who follows me on Twitter, and who just happens to work in one of the largest Watson Fothergill buildings in the city) I was able go inside the building on King Street now known as Fothergill House. It was built as a Department Store for Jessop & Son circa 1895.

Some changable summer weather struck just as I arrived to meet Alec to explore the floors at the top of the buildings but we pressed on and I took a few photos as we went.

At the firm where Alec works they have meeting rooms with appropriate names. (They’ve also commemorated Zebedee Jessop, one of the founders of the Store.)

We went up two flights of stairs to access the rooms that now hold tanks and heating. I think originally they were part of the staff accomodation.

The paint was peeling off, strip lights had been added and it was a bit dusty. There were some exploratory holes in the walls in places, but otherwise the structure looked in decent shape.

There seemed to be original leaded windows on each side, and lots of strudy woodwork to support the structure.

Some of the views of Nottingham are blocked by more recent buildings, but you can imagine that the view from here (and from the tower itself) was very impressive when this was built in 1895 – it would have been one of the tallest structures around.

Queens Chambers shares some of the features of Fothergill’s late 1890s Vernacular Style with Jessops and was the next building he built.

We kept going up so I could have a look inside the tower. We didn’t dare go inside it, but I could see that there was a viewing platform at the very top. Was it just built for the view or did it ever have another purpose?

I imagine that the rafters and timbers here are a larger version of the kind of craftsmanship that Fothergill had built into the turrets on his other buildings.

After a look around inside, we braved the rain to have a look out on the roof platform. There were metal walkways, so it was very safe to explore inbetween the air-con units added to the modern offices.

Jessops was expanded to the back of the site in 1933 when the stone became part of The John Lewis Partnership. From this quick inspection, I’m not sure if the flat roof is part of that or a more recent renovation.

Pleasingly the back view of the tower had all the elements of Fothergill’s style that you would expect, large chimneys, orange bricks arranged between black timbers, large dormer windows…

I love the details of brick nogging and big dormer windows, that hardly anyone will get to see.

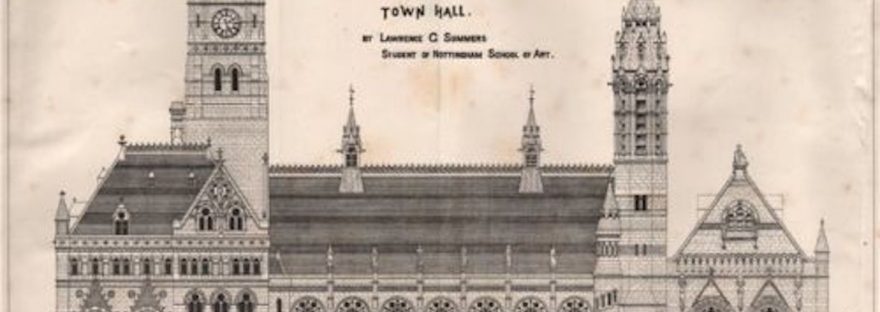

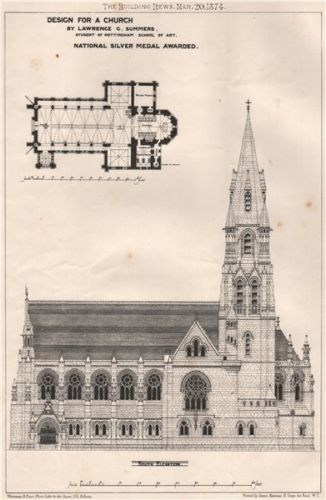

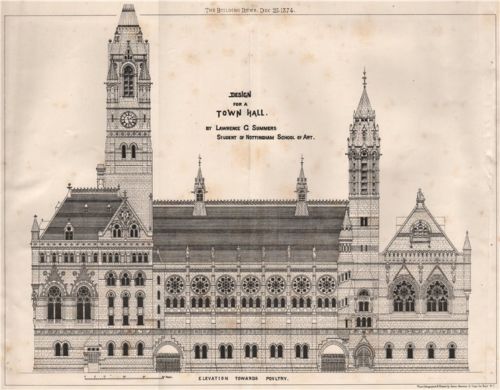

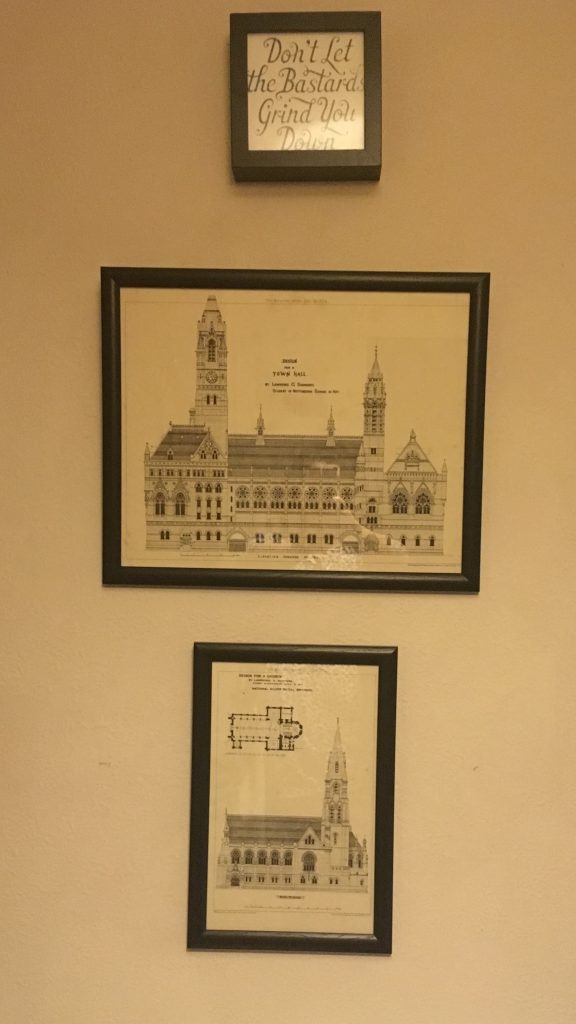

Huge thanks to Alec for taking me up to the roof and letting me look around as well as to his firm for sparing him the time, and David on reception for showing me some of the Fothergill pictures which decorate the interior.

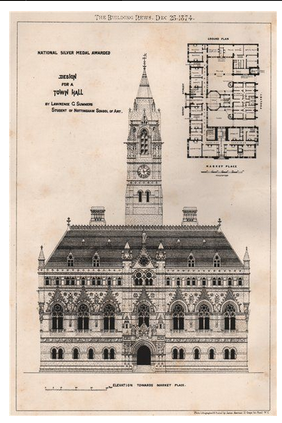

One last Fothergill link I’ve found while digging in the British Newspaper Archives: Lawrence Summers (Fothergill’s right hand man) attended the funeral in 1919 of William Jessop (who had succeeded his father Zebedee Jessop to run the firm).

Learn more about Jessops and Watson Fothergill’s buildings in Nottingham on the next Watson Fothergill Walks in August. Tickets here.