Plus Nottingham architecture events now booking.

My next Vat & Fiddle talk, on Watson Fothergill in the Park Estate, is now sold out. However, if you’d like to book me to give a talk to your group or club, please do not hesitate to contact me.

The first few tours of the year are filling up nicely – Deco in the Details Part 1 on 15 February is now full, but there is space left on Deco in the Details Part 2 on 29 March, and on the Watson Fothergill Walk on 22 February and 22 March. There will be more tours throughout the year, with The Carrington Crawl and Hine Hike also returning, so keep an eye on these emails for future dates.

The weather has not been particularly conducive for tours this month, so I took a day off for a wander around Beeston. (This is not a guided tour, just something I do!)

Beeston’s history is well-documented, and the Beeston Civic Society have been doing great work. If you live there or visit, you’ll know that there are loads of cafes and bars, interesting shops and charity shops. A few buildings caught my eye…

As a former Library Assistant and full-time bookworm, I made a beeline for Beeston Library. The building on Foster Avenue was designed by the County Architect E. W. Roberts in 1938. He was also responsible for West Bridgford Library. The builders of the Library, local firm Hofton & Son, also built Beeston Town Hall, which is now used as a church, and sits opposite. It opened in 1938 and was designed by the architects Evans, Clark & Wollatt with H.H. Goodall. It has a solid Neo-Georgian look with Art Deco details.

After a very nice coffee at Greenhood, itself in a former Birds the Confectioners shop on the High Road, our daunder** took us past the former Primitive Methodist Church on Wollaton Road. This 1882 building was one of many Victorian-era Methodist churches by Nottingham architect Richard Charles Sutton.

R.C. Sutton was a very prolific architect in his day; his buildings can be found all over Nottingham and outlying areas. I’m hoping to explore his work and his connections to Bromley House Library, where he had his office, further this year.

Back on the High Road, the former NatWest Bank stands out. It was originally built for the Nottingham and Notts bank, 1905-08, and was likely designed by the Coalville architect Thomas Ignatius McCarthy. The Pevsner guide describes it as “abstracted Neo-Tudor.” It ceased to be a bank in 2023 and is now a kitchen showroom.

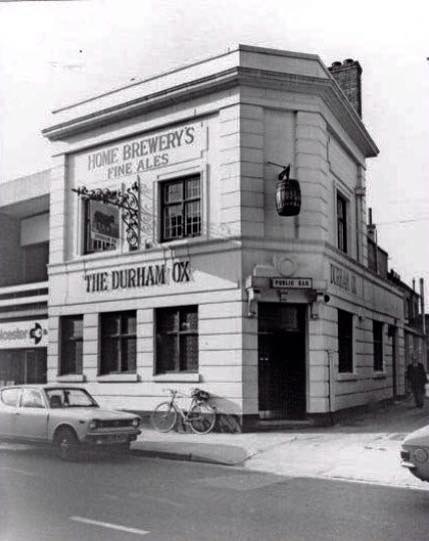

Further down the High Road, the familiar Home Brewery lettering on a white building caught my eye. The Pudding Pantry cafe was previously The Durham Ox pub.

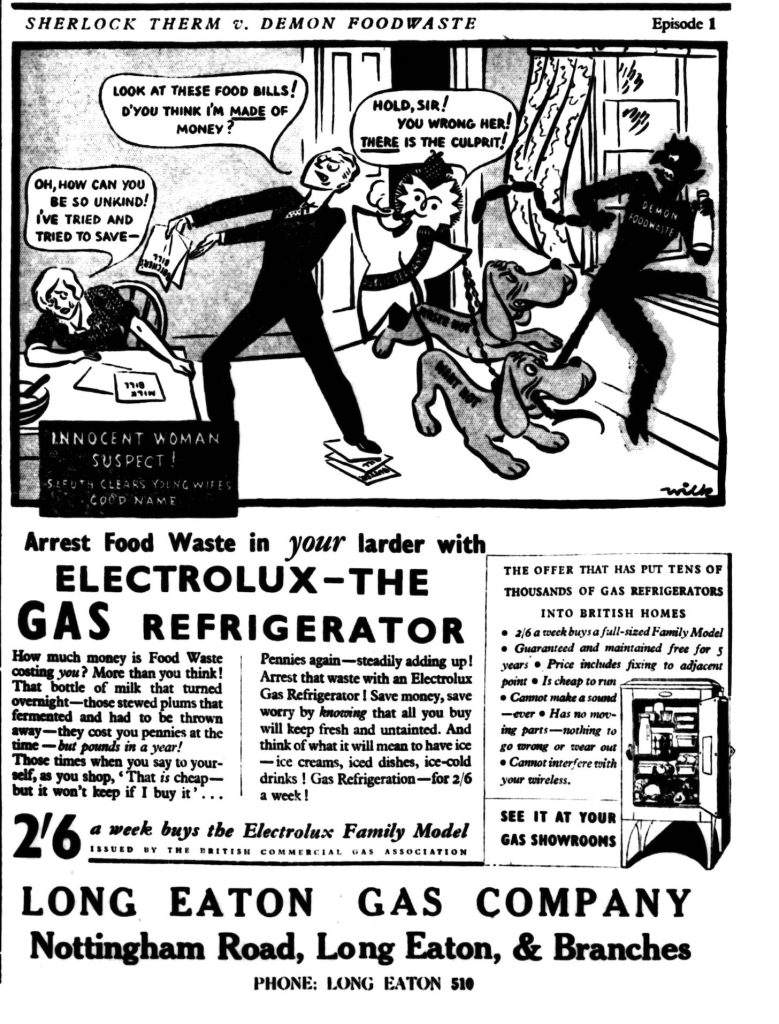

A very detailed history of the pub can be found on David Hallam’s Beeston History website. The present building was built in 1925, and was one of many pubs rebuilt by the Nottingham architect Albert Edgar Eberlin, as mentioned in my Art Deco Pubs talk. Eberlin also worked on The Fox, The Royal Children, The Beechdale and many more pub buildings around Nottingham.

Another Deco-era building I noticed, the recently closed Poundland, was in fact a former Woolworths.

This was Woolworth’s store 578 and was completed in 1934 by their in-house architect, Harold Winbourne. I noticed the parapet and margin glazing in the metal-framed windows. Head over to the Woolies Buildings website for archive pictures of this one in its former glory and to Building Our Past for shop architecture historian Kathryn A. Morrison’s in-depth look at Woolworths and their architects.

Does your neighbourhood have any buildings that catch your eye? Look up and see what you can see next time you’re out. Or if you have a building you’d like me to research – get in touch.

* Bimble; English, informal: a leisurely walk or journey.

** Daunder; Scots: to stroll, saunter or wander aimlessly.

Thanks for reading Watson Fothergill Walk – Lucy Brouwer! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.