Sometimes I’m lucky enough to be invited to explore Fothergill buildings. The latest of these was The Red House, on Cator Lane, Chilwell.

The Red House is listed in the Fothergill Catalogue as a “Minor Work”, as it was not originally built by the architect. However, the additions he made to the property are quite extensive.

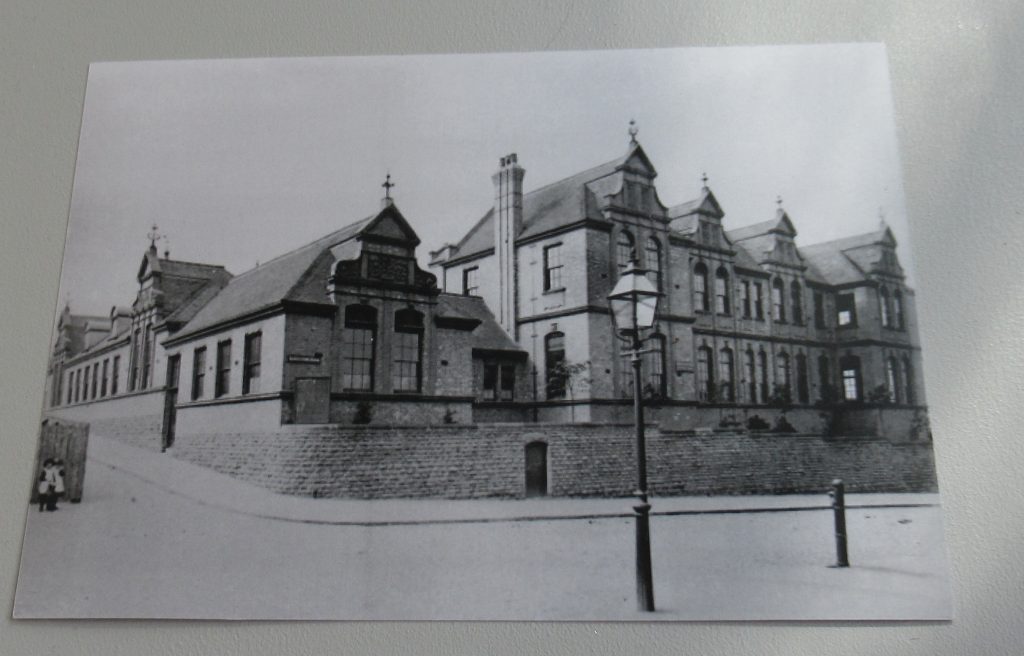

With its very tall chimney and red bricks, The Red House stands out amid the 1930s suburban semis that make up the rest of the street. Indeed, for a long time the original house (then called Hill House) was the only building on this part of Cator Lane, it is visible on maps from around 1850 – it may have been built even earlier, around 1840 from the style of the windows in the original parts of the house.

The plans for Fothergill’s alterations were submitted in October 1895, approved in November and presumably carried out shortly after. The extension is shown on the 1900 OS map of the area. After the work, the house is called “The Red House” on maps and it is apparently the only substantial dwelling on Cator Lane until about 1930. I’ve found advertisements in newspapers from 1933 offering houses for sale (for £550 per house) on The Red House Estate on Cator Lane, most of the houses nearby look as if they were built around this date.

Ian, the present owner of The Red House, gave me a tour and told me what he knows about the history of the building.

The house had been a parsonage and the client for the extension work was Frederic Chatfield Smith (1824-1905) of Bramcote Hall, at one time an MP for the area and the head of Smiths Bank in Nottingham. However, Smith did not live in the house.

There is a plaque commemorating Smith in the nearby Christ Church in Chilwell, he endowed the church but this wasn’t until 1903. He was known for his charitable work as his obituary in Nottingham Evening Post, 22 April 1905 notes:

“He manifested a warm interest in religious and philanthropic work, being an ever-generous subscriber to charitable and other institutions. He was a patron of the living of Bramcote with Attenborough, and he exercised discriminating influence in church matters.”

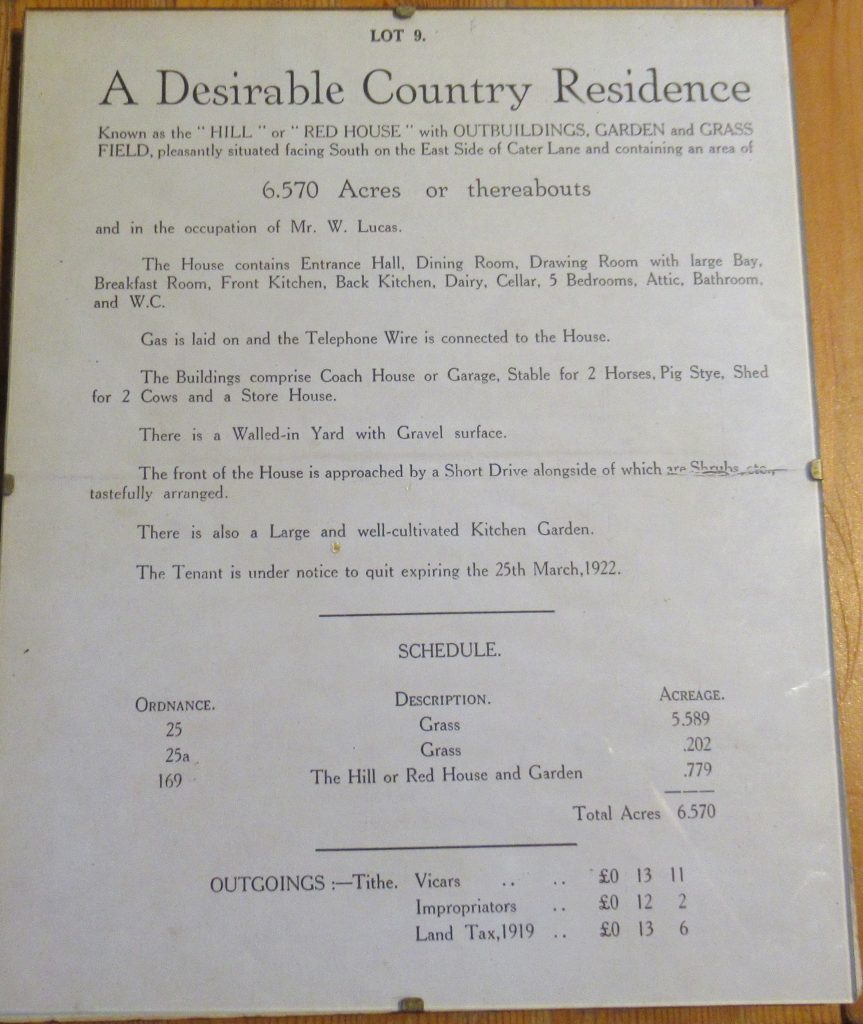

So did Frederick Chatfield Smith extend the house to encourage a new vicar to move to Chilwell? It seems that after the improvements the house remained as a small farm, with a quantity of pasture land and some animals. Ian has an advertisement that describes the house when it was offered for auction in the 1920s.

I’ve found that in 1864, the house had been lived in by the then late Joseph Morris – cited in a marriage announcement for his sixth daughter Pattie.

In 1889, the householder was The Rev. James Crabtree – so it was presumably still a parsonage at this point.

After the extension was added, I’ve found a few of the residents and some information:

Around 1898-1899 G.W. Baxter, his wife, son and daughters can be found at the house. Baxter and family rode with the Earl of Harrington’s hunt in 1898, and in April 1899 GW Baxter could be found selling a horse at the Black Boy Repository (behind the hotel?) in Nottingham. In November 1899, both he and his servants donated to the Shilling Fund.

Brigadier General Charles Tyrell Shipley CB (1863-1933) was another resident of the Red House. I’ve found a couple of photographs of him: here in uniform and here as a younger man, and something of his war record, he seems to have had an illustrious military career, commanding the 46th North Midlands Division and according to his obituary in the Nottingham Evening Post (13 Nov 1933) he lived at The Red House “before the war” (WW1).

Newspaper classified ads are another way of discovering who lived in a house. Between 1915-1918, the Barnett family various posted notices for the sale of a Great Dane puppy, an appeal to find their lost Airedale bitch, Jessie, and a “wanted ad” for a Daily Help or a good cook-general.

In both September 1919 and December 1921 the house was part of a selection of properties and land up for auction (in 1921 the tenant was cited as Mr W. Lucas). I believe the poster Ian showed me (pictured above) is from around this time.

Between 1923 and 1933 Kennedy William Harrison and his family were resident in the house – for several years running they annually offer for sale a litter of pigs (there was a pigsty outside the house, which is still recognisable among the outbuildings) as well as a litter of retriever puppies and “50 second season fowls in full lay” (Present owner Ian’s lockdown project was to install a small coop with hens!).

There are also reports of Mrs Harrison being involved in a motor bus accident in 1923 when a Barton Bros bus ran into a telegraph pole in Beeston. Despite being a “victim of the mishap” Mrs Harrison was “progressing satisfactorily” at the time of the report in the Beeston Gazette and Echo (6 October 1923). A company, Harrison and Hill Ltd, was formed in 1932, with Mr Harrison going into business with a certain Miss Gwendoline Hill in a firm of manufacturers and dealers of clothing and wearing apparel.

Between around 1933 and 1936, The Red House Estate was being developed on surrounding land off the newly created Brookland Drive. The builder Cecil C. Blythe advertises houses in local papers with tag lines including, “Have you visited The Red House Estate, Cator Lane? If not, why not?” the houses were “modern and labour saving” (Beeston Gazette and Echo, 4 Nov 1933). All these nuggets were found using the British Newspaper Archive.

Ian was keen to point out that The Red House exhibits some characteristics that bring to mind the Arts & Crafts movement – Fothergill’s attention to detail, fondness for decorative elements and good quality materials suggest at least a knowledge of William Morris and his Red House – now a National Trust property in Bexleyheath, on the outskirts of London. But “The Red House” is a common name for properties that are this colour – Fothergill’s fondness for the distinctive Mapperley Bricks might just as well be the origin of the name.

Inside the house, there are some quirks of design like the decorative coving in the Fothergill drawing room, and a door that has a frame at an angle to accommodate the staircase. Fothergill appears to have moved the stairs from what was the front of the house to the back (except this is now used as the front!). It was hard to photograph and it would be useful to have the plans – if anyone with knowledge of Chilwell history knows where they might be, then please let us know!

Huge thanks to Ian Paul for inviting me to look at his house!

If you live in a Fothergill building, or if you have a house whose history you’d like to explore, then Lucy might be able to help with research – please fill in the form on the contact page to send a message. Tours will be back in 2022!