I’ve added some more titles from Nottingham Civic Society to the online shop .

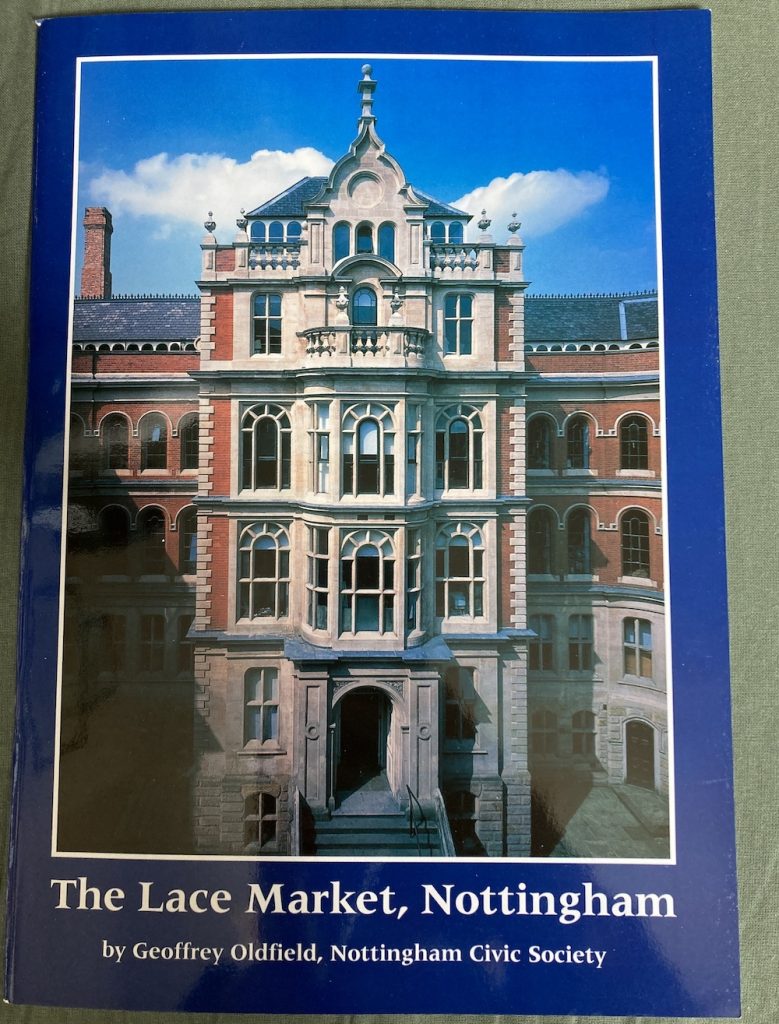

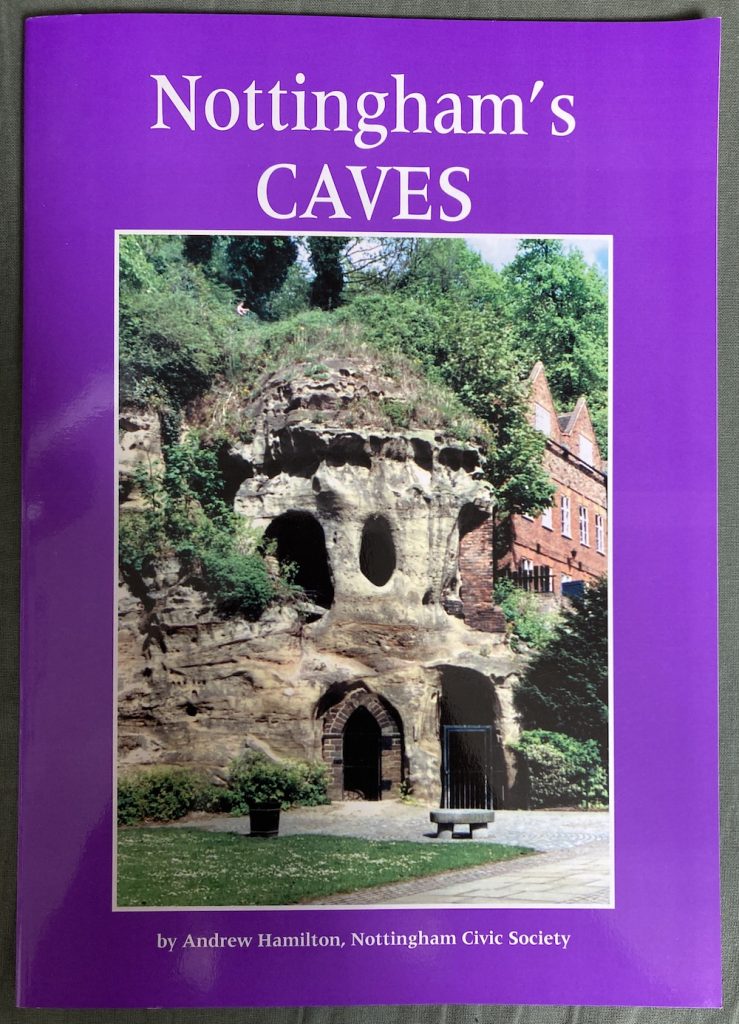

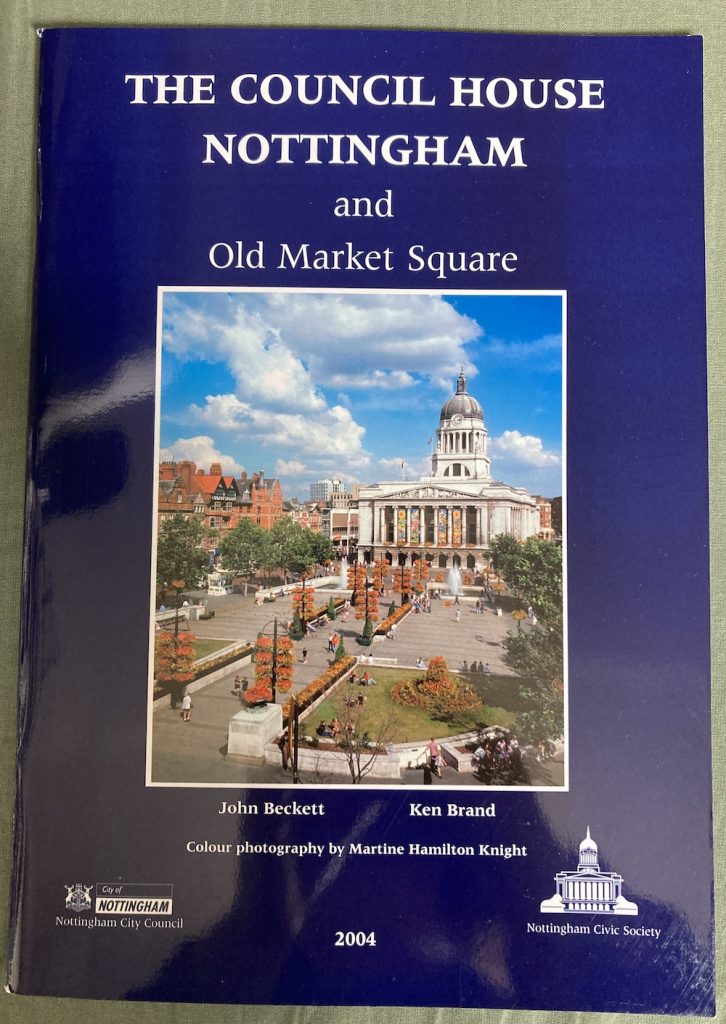

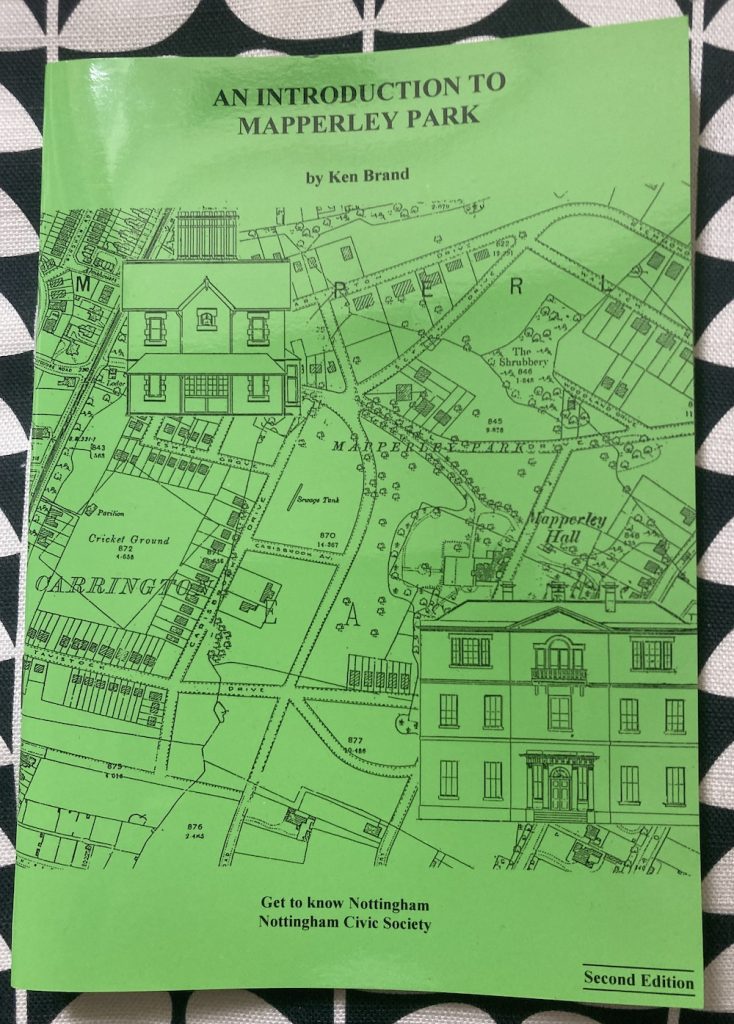

These include the late Ken Brand’s pamphlet on Mapperley Park Estate, Geoffrey Oldfield’s The Lace Market, Nottingham and Andrew Hamilton’s look at Nottingham’s Caves. There are also just 2 copies of the commemorative book on The Council House and Old Market Square, which was put together by The Civic Society in 2004 to mark it’s 75th anniversary.

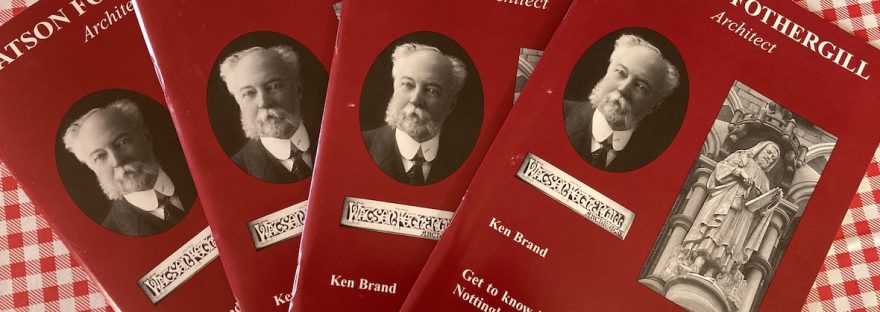

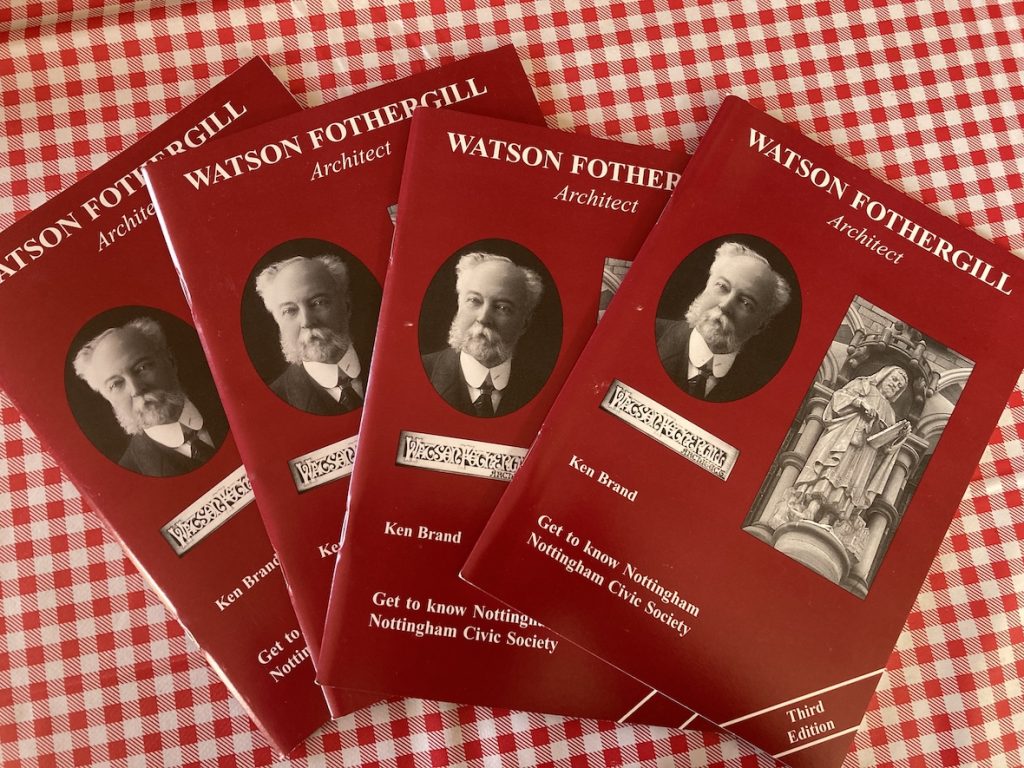

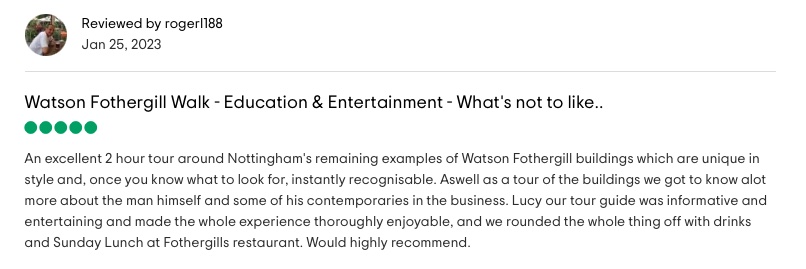

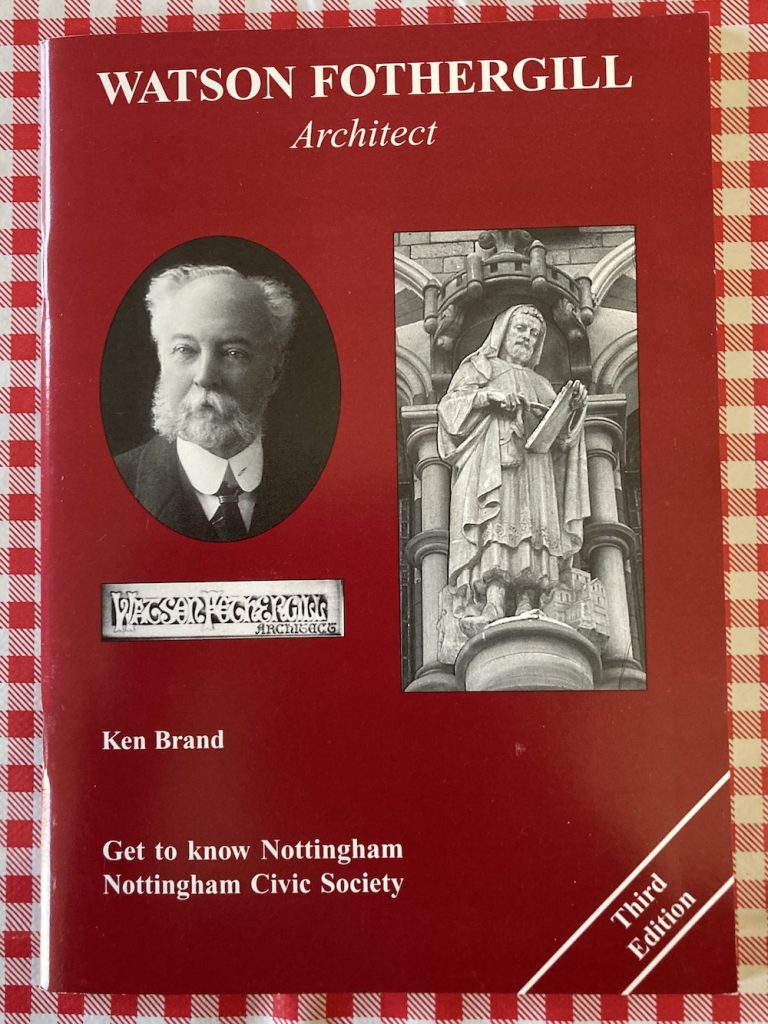

There are very limited numbers of each book at the moment and there are also some copies of Ken Brand’s Watson Fothergill book available. Postage is at the flat rate of £2.70 which allows you to purchase multiple books.

Visit the SHOP.

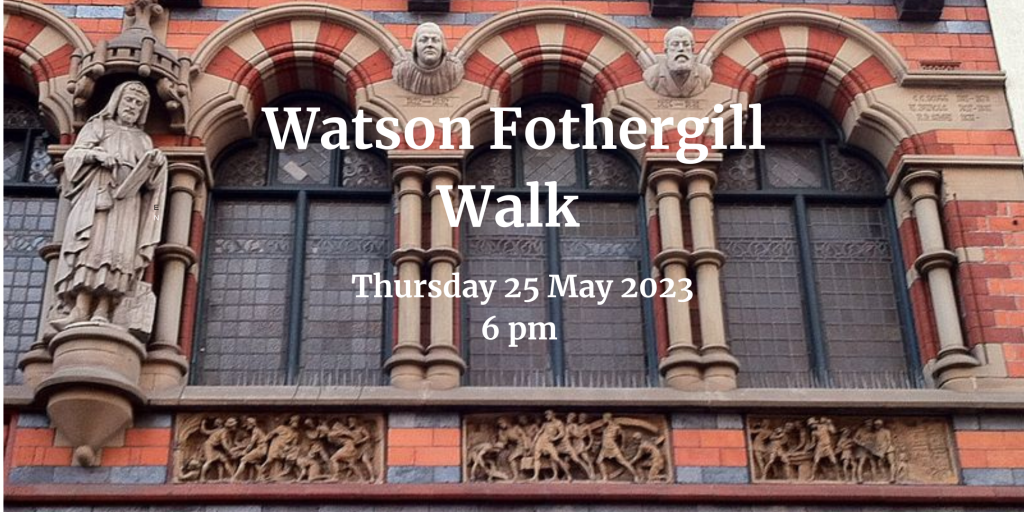

Walk tickets are still available via EVENTBRITE