Over on Instagram you might have seen an account called Inside Elm Bank, here the new owners of a Victorian villa in Mapperley Park are documenting their efforts to restore it to something of its original character. The house has some distinctive features that might be familiar to Fothergill-spotters. However, in this case, the alterations to the front of the house, the addition of a breakfast room, kitchen and scullery with bedroom over, were carried out by Watson Fothergill’s chief assistant, Lawrence George Summers.

Evidence of this work was identified by Darren Turner in his Fothergill; A Catalogue of the Works of Watson Fothergill, Architect, in the section on work signed off by L.G. Summers. The house at 9 Elm Bank, which for many years was known as Elm Bank Lodge, was already in existence before it was altered in 1893.

I’ve had a look at the evidence to see if I could find more information on who built the house, who lived there and who commissioned the alterations.

Thanks to the new owners for a few new clues… here’s my attempt at A House Through Time…

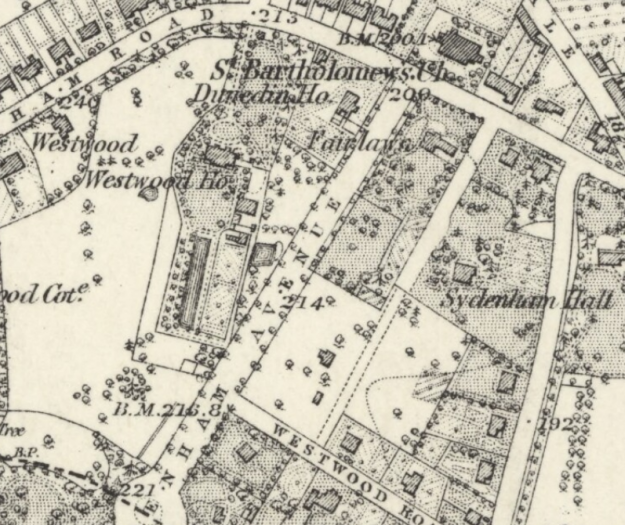

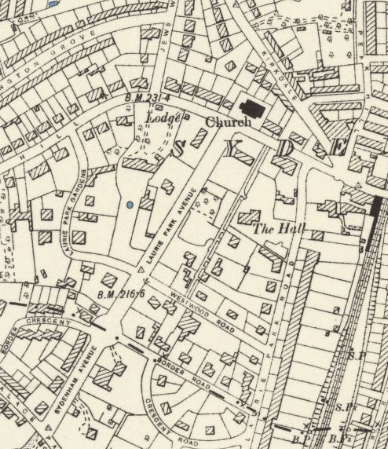

1875. The land that the house was built on was part of land owned and sold by Edwin Patchitt (1808-1888). Patchitt was a solicitor, clerk and land owner (and Mayor of Nottingham in 1852) who was responsible for laying out the Church (Rock) Cemetery (in 1851). Patchitt’s land also included the plot sold to Fothergill Watson in 1870, where he built his own house at 7 Mapperley Road (now Fothergill Court). Patchitt lived at Forest House, which was adjacent (later owned by Thomas Birkin, it was donated to become the Children’s Hospital 1899-1978). Leonard Lindley (1835-95), mentioned in the conveyance deeds was also a JP (Justice of the Peace)like Patchitt, he lived on Mapperley Road (in 1885 at Redcliffe House). I have not been able to trace the William Ellis who was also mentioned in the documents.

1880. The land was again conveyed between William Ellis, James Bingham, Joseph James Acton & John Eley Bryan.

It appears the original house was built some time between this point and the 1881 census when Joseph James Acton and his family were listed as being in residence. Taken in April 1881, the census listed Joseph James Acton (1837-1887) Building Surveyor to the corporation of Nottingham, his wife Sarah E Acton, their baby daughter Ethel, along with a cook, housemaid and groom. (Acton was brother of Frederick Acton, solicitor who lived at Elm House.)

John Eley Bryan (1851-1918) was also listed as living on Elm Bank, but not in a census year and the number of the house is not mentioned, which leads me to believe that the original plot may have been split. There are now 3 houses quite close together on the site. John Eley Bryan was Accountant to the Corporation of Nottingham (aka The Boro Accountant). His wife Mary died in 1882 and shortly afterward there was an advertisement for the Freehold of his villa on Elm Bank but the number was not mentioned, it had three floors which makes me think it was the house next door.

I have found conflicting information from newspapers and trade directories which point to other names who might have lived at 9 Elm Bank – in 1883 there was mention of Stephen Waine (1837-1889) of Barker and Waine Lace Dressers (but other evidence – in newspaper announcements – points to Mr Waine living around the corner at Claremont on Redcliffe Road.) Another name mentioned by trade directories in 1885 was William Henry Butler. The only evidence I can find for him was a report of a boot and shoe maker of that name being sued by the Nottingham Patent Brick Company to recover the deposit they had payed to him for the sale of a villa and grounds at Mapperley. As the NPBC could not use the land as a brickfield they wished to cancel the sale. I don’t believe this refers to Elm Bank, but no address is mentioned.

The next piece of solid evidence was a newspaper advertisement from 1887 “Good general servant who can cook nicely: two others kept; six in family; first-class character required. – Mrs Willatt, 9 Elm Bank Mapperley Road.” Mrs Willatt was Mary Jane (nee Attenborough) wife of John Willatt (1849-1901), Wine and Spirit Merchant of J Willatt & Co, 17 Chapel Bar. (He had recently taken over the firm from his father Issac Willatt). By 1891 and the census, the Willatts were living at Pelham Road.

The 1891 census offers the residents of 9 Elm Bank to have been the Holland family. William Holland (1835- 1907?) an accountant born in Lancashire, his wife Hannah and their children Arthur aged 18 working in a Lace Warehouse, Jessie aged 15, Edwin aged 12 and Elizabeth Newbitt a 16 year old servant. By 1901 William had become a school teacher and the Hollands were living at 17 Private Road, Mapperley Park.

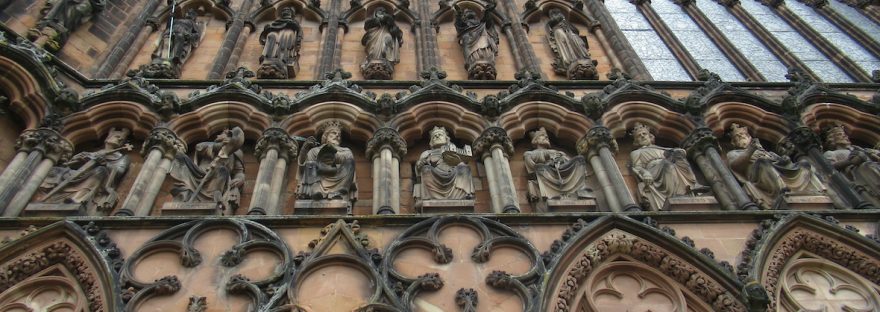

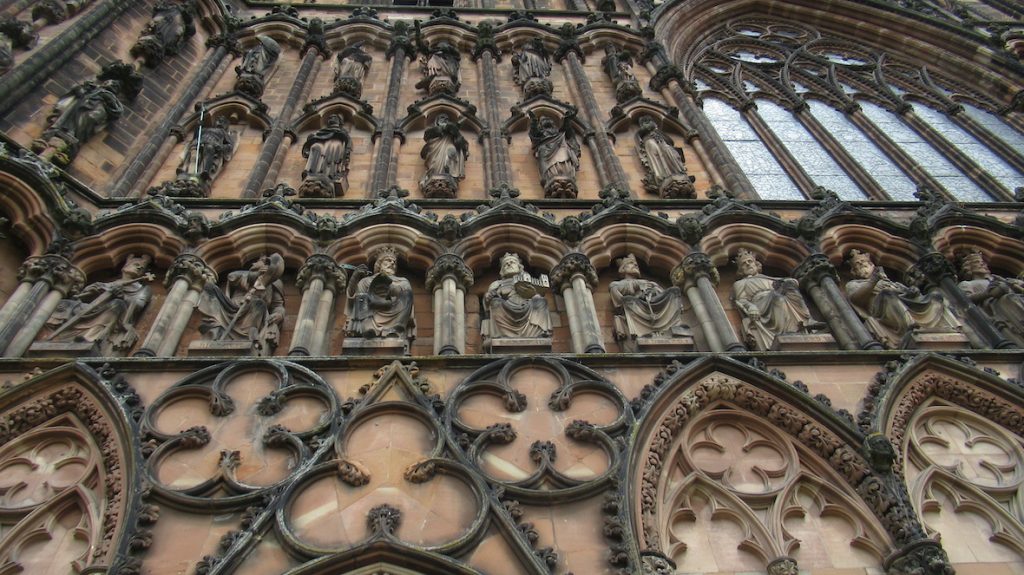

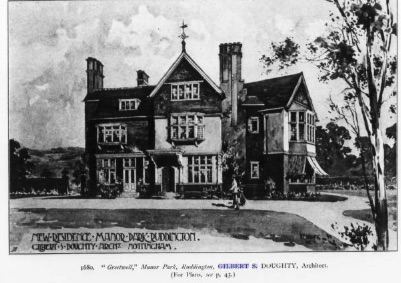

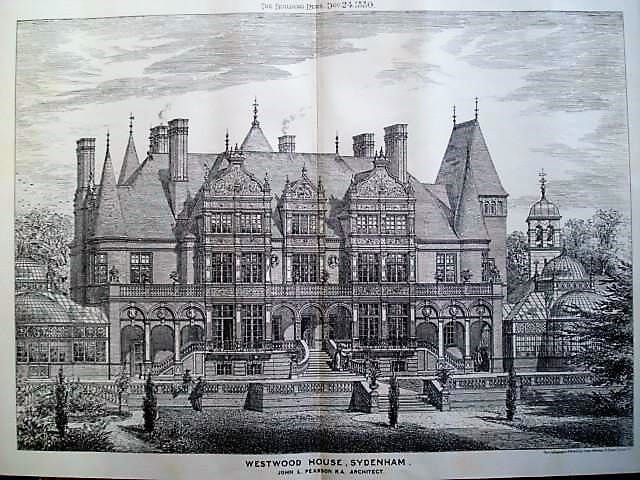

In 1893 the plans were submitted for the alterations to the house. Lawrence George Summers, FRIBA signed as architect. Summers worked as Fothergill’s chief assistant. Of all the works signed as solely by LG Summers, the additions to this house are closest to the work of Fothergill in appearance. The builder was listed as R. Howitt and the client was Mr Thomas Jopling.

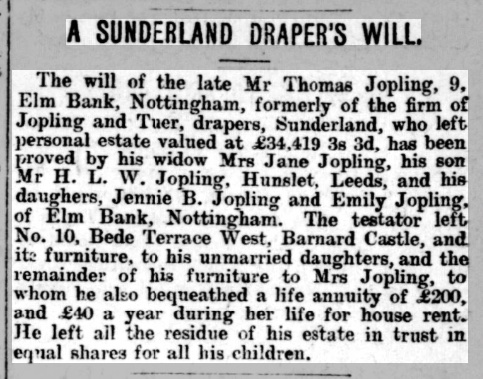

Thomas Jopling (1837-1897) was resident in the house 1895-1897. He was a Draper from Sunderland. A little searching turns up evidence that his firm was Jopling and Tuer, a well known Sunderland firm with a large shop. What was he doing in Nottingham? He writes to the Newcastle Journal in February 1895 to remark that the birds in Nottingham are showing signs of spring… “The rooks are now assembling on the trees, and we soon will see those sable gentlemen in full swing reconstructing their rookeries.”

Thomas Jopling died while residing at 9 Elm Bank in 1897. He left his widow Jane Jopling, eldest son Hugh, daughters Jennie, Emily, Kathleen, Marion, Eliza, Margery, and younger sons Tom & Mark. They -return to Sunderland after the death of Thomas. Hugh was already married and had moved to Leeds. In 1899 Emily married a farmer, Stanley Beardall and they lived at Stanford on Soar, Notts. with her mother Jane and her brother Tom. They later moved to Yorkshire.

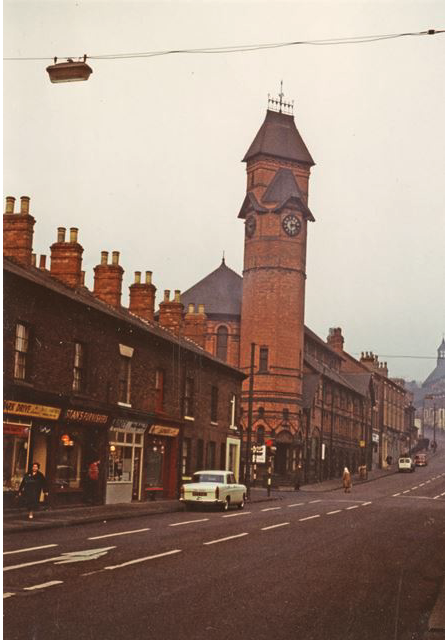

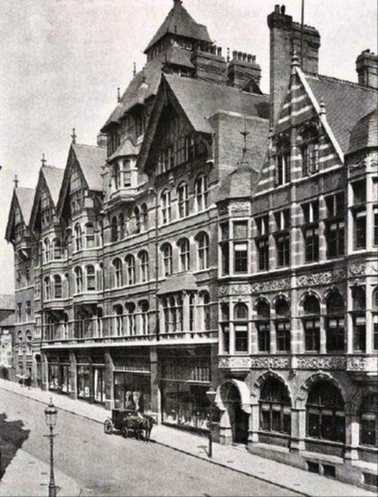

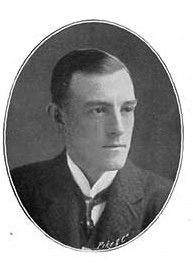

From 1898, the house at 9 Elm Bank was occupied by Arthur Ernest Blake (1866-1935) and his family. Arthur E Blake (from 1920 Sir Arthur E Blake KBE) was a stockbroker and some-time estate agent. His place of business was briefly 2 Victoria Street (he was working from The Nottingham Club, or at least using it as an address) and then from 1897 he worked in Prudential Buildings (Alfred Waterhouse’s impressive building at the intersection of King and Queen Streets in the centre of Nottingham). He was a member of not only the Nottingham Club, but also the Borough and Constitutional Clubs. He had a long association with Nottingham Rowing Club and the Conservative Association.

In 1895 he had married his wife Florence Emily Blake (1870-1942), her father John Angrave Howitt(1829-1899) had been a Lace Manufacturer and was possibly later the publican of the Albert Hotel. Florence had at least 3 sisters and a brother. They were mentioned in newspaper reports of the sister’s marriages and wedding receptions held at Elm Bank in 1905 (Hilda Constance Howitt and Edgar Horne), 1908 (Maud Howitt and Henry White Thompson) and 1909 (Dorothy Howitt and Thomas Chambers Dawson). In all three of these reports the house was called “Thornhill”.

In 1911 the census records the residents of 9 Elm Bank to be Arthur Ernest Blake, Florence Emily Blake, their children Majorie, Olive Joan and Kenneth Arthur (their elder sons Geoffrey and Robert having already left home), the servants at this time were a cook and two house maids.

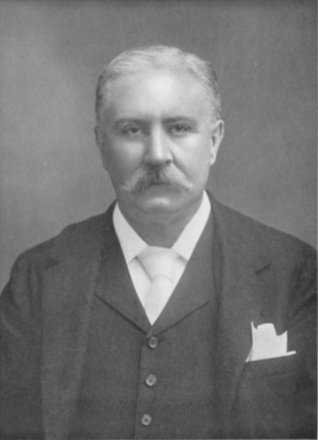

Sir Arthur was knighted in 1920 and was the Hon President of the Nottingham Savings Bank. His portrait is held in the Lloyds TSB archives and the National Portrait Gallery.

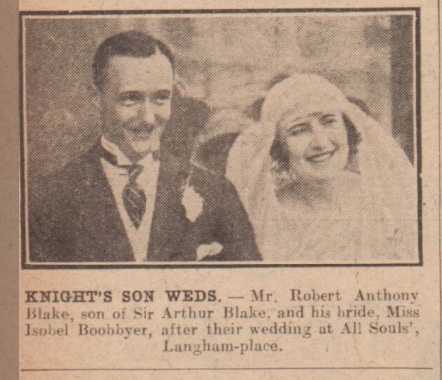

Sir Arthur Blake was High Sheriff of Nottingham in 1924 and by this time the family had moved out to West Leake manor (from 1915). The Blake’s eldest son, Geoffrey Stuart Blake (1896-1917) was killed in action in WW1. In 1925 their second son Robert Anthony Blake (1897-1928) married Annie Isobel Boobbyer – Annie Isobel was the daughter of Annie Forbes Watson Fothergill Boobbyer and Dr Phillip Boobbyer, Medical Officer of Health for Nottingham – making her Watson Fothergill’s granddaughter. Fothergill’s own house on Mapperley Road was a stone’s throw from Elm Bank. In 1928 Robert was killed in an aeroplane accident when flying with Nottingham Aero Club. They had one son, Philip Anthony Blake, born 1926. The wedding in 1925 had been quite an event – this photo captures some of the glamour.

The Blake family were commemorated in the church at West Leake with stained glass and plaques. Lady Florence Blake went to live in the Park Estate at Fairholme, 13 Lenton Road after Sir Arthur’s death in 1935 while on a voyage to Durban South Africa. She died in 1942.

After the Blakes, 9 Elm Bank was home to James Allan Battersby (1871-1931) his wife Lois Allen Battersby and their 5 daughters – Edith Mary, Marguerite, Kathleen Ada, Joyce Allen and Helen Houghton Battersby. J. Allan Battersby OBE was a barrister who had been a famous Poor Law Officer in London, who came to Nottingham to work as Clerk to the Guardians of Bagthorpe Infirmary, he died suddenly in 1931 having become Superintendent Registrar of Births and Deaths for the City and Clerk to the Public Assessment Committee. The family had already moved out of Elm Bank to Magdala Road some time after 1927.

In 1936 the house was briefly empty (there was a report of a burglary from the empty house of a sideboard top). Then in 1937 the next known residents were Bernard Savage (b.1888) and his wife Marian, nee Walton (b.1894). They married in Halifax, where they were from, in 1916. Bernard Savage had come to Nottingham to be manager of the new Halifax Building Society branch opened in June 1937 at Halifax House, Milton Street in Nottingham (the building is now home to 200 Degrees Coffee’s 3rd Nottingham Branch). Bernard was in Nottingham until at least 1947 as district manager of the Halifax.

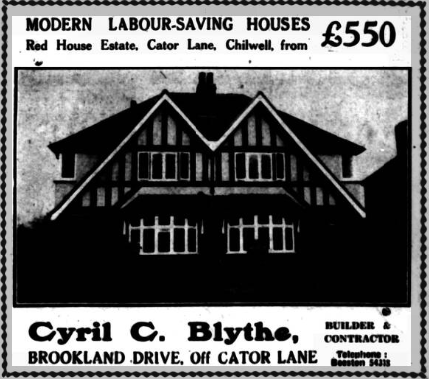

The next trade directory I was able to find was from 1950 and it appears that 9 Elm Bank had been turned into 3 flats with the residents listed as at number 9 Cyril E Langford, at 9A Arthur Gosling and at 9B Hugh S McAllister. Later, into the present decade, Elm Bank Lodge was run as a Bed and Breakfast when the owner was the late Mr Andrew Stewart.

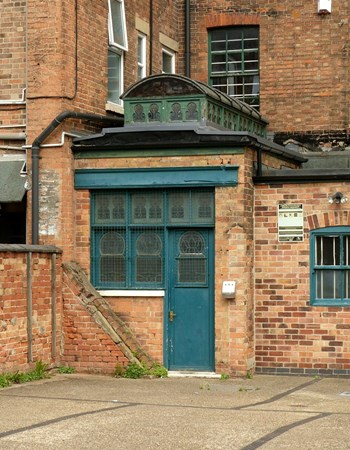

Not much of the original interior of the building has survived, but it’s possible that the copper fireplace in the Breakfast room could be part of LG Summers’ decorative scheme.

Follow the progress of the renovation of the house at Elm Bank on Instagram and you can find me at watsonfothergillwalk.

If you have any information on previous residents of Elm Bank or you would like me to research the history of your house, please send a message here.